Newes From The Dead by Mary Hooper

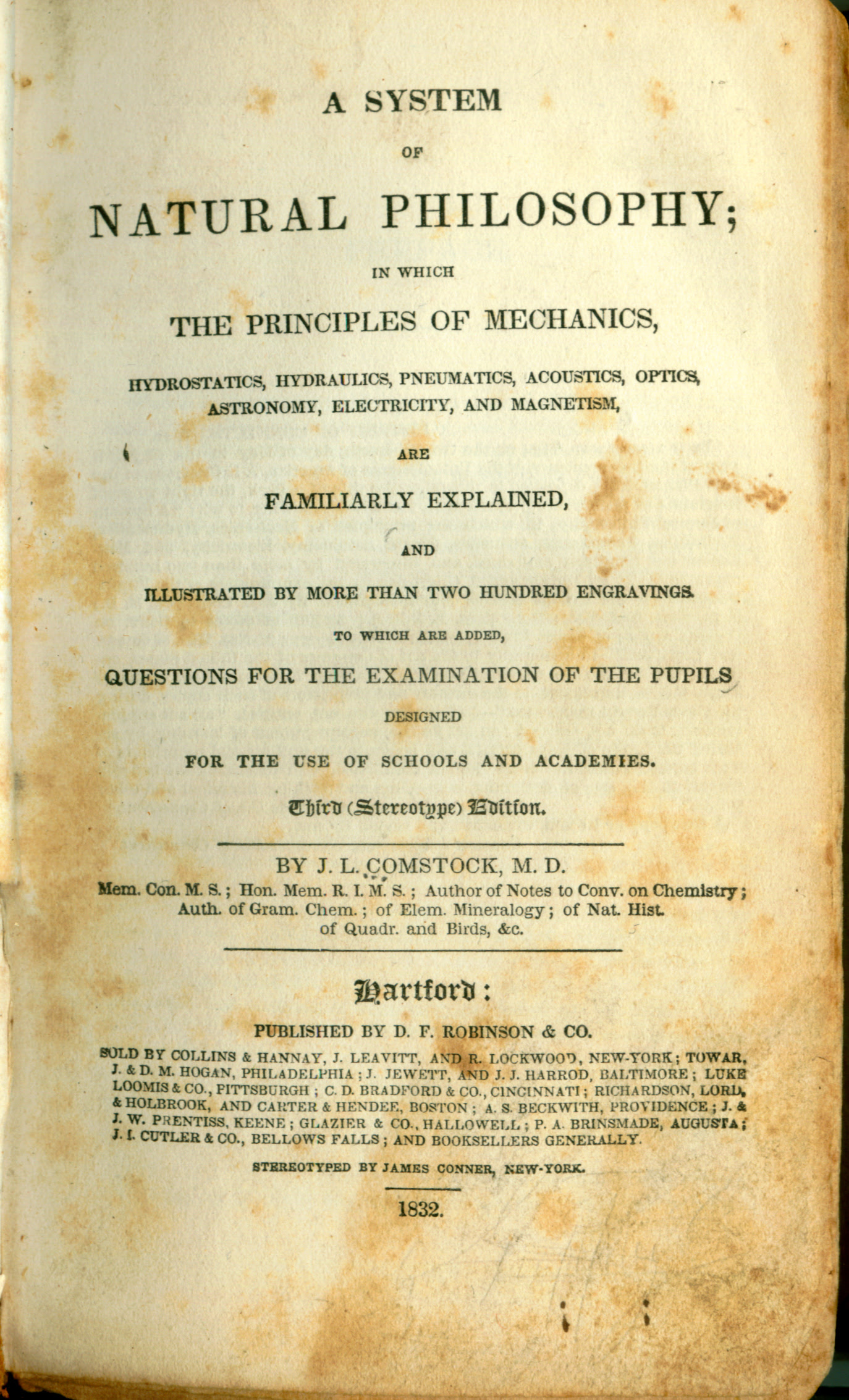

Intriguing and captivating.-Celia Rees, author of Witch Child WRONGED. HANGED. ALIVE? (AND TRUE!) Anne can't move a muscle, can't open her eyes, can't scream. She lies immobile in the darkness, unsure if she'd dead, terrified she's buried alive, haunted by her final memory-of being hanged. A maidservant falsely accused of infanticide in 1650 England and sent to the scaffold, Anne Green is trapped with her racing thoughts, her burning need to revisit the events-and the man-that led her to the gallows. Meanwhile, a shy 18-year-old medical student attends his first dissection and notices something strange as the doctors prepare their tools . . . Did her eyelids just flutter? Could this corpse be alive? Beautifully written, impossible to put down, and meticulously researched, Newes from the Dead is based on the true story of the real Anne Green, a servant who survived a hanging to awaken on the dissection table. Newes from the Dead concludes with scans of the original 1651 document that recounts this chilling medical phenomenon. Newes from the Dead is a 2009 Bank Street - Best Children's Book of the Year. Editorial Reviews From School Library Journal Grade 8 Up--A grabber of a premise: It's England, 1650, and as the dissection of an ill-fated 22-year-old servant woman newly unstrung from the gallows begins, the participants detect the cadaver's eyes flickering. Hooper alternates perspective from Anne (the not-actually-dead corpse), who flashes back to explain how she ended up there, to that of a young intellectual attendee of the dissection, a sympathetic stutterer named Robert. Anne's story, rife with gruesome scenes of Puritan-era life (e.g., a rat-infested prison, a bloody miscarriage in a dirty privy) trumps Robert's drier account of the discourse among various distinguished intellectuals of the day, unless readers are well versed in the period's historical details (e.g., when Christopher Wren is teased for his poor poetry). The resulting back-and-forth of the two narrators makes for a poorly paced read, but the pervasive sense of injustice and indignity is vibrant enough to buoy readers through to the unexpectedly positive ending. Loosely based on a true story--hence the title, taken from broadsides published at the time--with a decidedly unromantic view of the era, this is a must-read for teens learning about Cromwell and the Puritan revolution, or for young feminists who appreciate narratives about the treatment of women in history.--Rhona Campbell, Washington, DC Public Library Copyright Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. Excerpt. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Chapter One It is very dark when I wake. This isn't frightening in itself, because most of the year I rise in darkness, Sir Thomas insisting that as much of the house as possible be put in order before any of the family is about. It is the quality of the darkness that is strange; blacker than black, soft and close about me. I go to turn my head toward the window, to see if any streaks of light can be seen in the sky, but my head doesn't move! I try again, and again. I lift my hand-or try to-but it doesn't want to obey me either. It must be that I am deeply asleep, in some sort of trancelike state, and aware that I'm dreaming. I think I will just waitfor it to pass so I may rise, dress, and go about my household duties. The waiting continues, and I feel nothing: neither cold nor warm, hungry nor replete. I just sense the blackness and soaring emptiness, but this is not too unpleasant. Some time later, though I cannot tell how long, I perceive movement across the backs of my eyes: four blurry white streaks, moving and gliding in the blackness. The streaks are feathery soft and remind me of doves, or of the soft, enveloping wings of angels. The blurry shapes dance across my eyelids, but when I try to stop them, to endeavor to focus on one and see if I can spy a shining halo or a gold harp, I find it impossible. I would like it to be angels that I dream of, for I know that would be very lucky. The Reverend Coxeter told us that. He said that no matter whether you are a scullery wench or a lord in his castle, you are truly blessed if you dream of angels. I have tried to dream of them ever since I heard that, but have never succeeded. Suddenly I remember something and want to scream with terror, and the blackness loses its velvety softness and takes on an aspect of such vast and unknown fears that the angels disappear. What I have remembered is this: the last time I saw the Reverend Coxeter 'twas not in church, but in a bleak yard in the icy rain, and he was entreating the Lord to have mercy on me, preserve my soul, and convey me quickly to paradise. Behind him had stood a great crowd of people, a man wearing a black hood, and a mighty wooden scaffold from which hung a heavy, knotted rope. And it was for me that all these were waiting, for I was . . . was about to be hanged. A terrifying thought comes to me: If this happened, am I now dead? No, I cannot be, for surely I can hear my heart thumping within me and echoing through my ears. Then is this the state that they tell us about in the Bible? Is this purgatory? I struggle to think, and recall that purgatory is said to be a painful state, with tortuous fires that cleanse the soul and bring it to righteousness. But how long does it last, this purgatory? A very long time, I think-thousands of years. My state is not painful now, though, so perhaps it might not be too terrible to be in purgatory. If it just means lying here quietly in the dark, it might be quite bearable. There would be no rising at two in the morning on washing day to soak the linen, no more scrubbing of the kitchen range until my hands bleed, no more going without food for breaking a plate and being unable to sleep for hunger. No more of that, either-that which Geoffrey Reade sought. As I think on this, I feel a shadow pass over my soul and know, without being sure of the circumstances, that he is inexplicably connected to my fate. I leave this thought atremble in the air and move on. Yes, I could, perhaps, bear purgatory. What I cannot bear . . . what I won't contemplate is . . . no, no! I won't let that thought in. But it comes anyway: What I could not bear, dare not consider, is the possibility that I'm not dead, but merely occupying a coffin, having been buried alive. I'm of a sudden desperate to come out of the trance I must be in, for surely-oh, surely-I am still in the little bedroom I share with Susan, and only deeply asleep. I urge myself on. In my mind's eye I picture myself pushing back my coarse blanket, swinging my legs out of the bed, and rising up, but though the urge is there, though I think I can perceive my muscles trembling with the effort to work, nothing happens and no part of me moves. I concentrate harder. Maybe sitting up is asking too much of my body. It will be enough if I can move my hand, feel what's around me: the straw mattress beneath me and the blanket on top. Once I know that I'm safe in my bed, I'll be content to lie here longer. I realize then that instead of being in my usual sleeping position, curled up like a wood louse, I'm lying straight and still with my hands crossed over my breasts. But this is not the usual manner in which I go to sleep . . . My limbs are not working, but my mind is going ahead, whirling on a dance, showing me images of the effigy in St. Mary's: a stone woman lying with her arms crossed over her cold stone body. Indeed! That's how they lay out the dead! I'm so disturbed by this image that for a moment I forget to breathe. I open my eyes; close them again. It makes no difference to the quality of the darkness. In fact I don't know if I'm opening my eyes or just dreaming I am. Am I asleep or awake? Alive or dead? Am I already a cadaver? My heart contracts with terror; there is a pain behind my eyes where I long to cry and a choking in my throat, but it seems that even crying is denied me. I begin to count to calm myself down. It is what I learned to do when Master Geoffrey was-but no, I cannot think on that yet. I wonder if this state, this condition of mine, is punishment for what I have done, for they are very hard with all who commit sin now, and I have heard of women who have fornicated being tied on a ducking stool and dropped into a pond, and those who have stolen being whipped around the village behind a cart. I have never heard of anyone being buried alive, though. I am very, very frightened. If I find out that I am buried, I'll claw at the wood that surrounds me, scratch the walls of my coffin, and break out. But what will I do then? If I'm a buried corpse, then I'm under six feet of earth and will never get free. Best to die quickly perhaps, to clamp my lips together, stop myself from drawing breath, and perish. In the blackness behind my eyes I try to see the blurry shapes again and turn them into comforting angels, but I cannot. Instead, chunks of my life come crowding in, clamoring to be heard, asking that they be considered in order to make sense of what's happened to me. So to start. It seems to me that going to work for Sir Thomas Reade was the beginning of it all, for that was how I came to be acquainted with his grandson and heir, Master Geoffrey Reade. His name evokes a terror, but I don't want to think why. Not yet. It is ahead of me though, a source of shadows in my head, waiting to be explored. But surely not all my recollections of that household are painful? There must be some that are not, I think, and I scuttle through my mind, throwing up memories like fallen leaves, looking for the bright ones. I have been working for the Reades since I was but a young child and, this titled family being the most noble in the area, 'tis thought a great honor to serve in their household. They own several estates in the county of Oxfordshire, and at first I worked for them at Barton Manor, a vast dwelling in Steeple Barton, the village where I was born. This village contains about a hundred people, who mostly work on the land, and is a small but ancient place with farms and cottages, bakers and blacksmiths. At one time it also contained a gracefully ordered church, but that was before Cromwell's men tore down its altar rails and broke its windows and pretty statues to turn it into a bare meeting house. Being well taught by my ma as to cleaning, washing, and the making of soaps and scented waters, I began working at Barton Manor as a scullery maid. This meant that I was the lowest person in the household and had to heed the wishes of everyone, which-if two persons had opposing wishes-was sometimes very difficult. I soon got to know the ways of the Reades, however, learned how to walk softly about the house so as not to disturb them, to bob a neat curtsy, and to discourse with lowered head if addressed by a member of the family. I can remember some good days then, for life seemed easier in the old house, and we servants had an amount of freedom. In Maytime there was always a pole on the village green to be danced around with ribbands. In the summer we'd while away hours cherry-picking in the orchard and gathering soft fruit-raspberries, strawberries, and mulberries-eating as much as we collected in our baskets. Later in the year, when the harvest was in, there would be a dance in the servants' hall, with a fiddler paid for by Mr. Peakes, the butler, with his own money, and we'd have a merry time dancing most of the night. We always sang as we worked at fruit picking or scrubbing or scouring: old songs we'd learned from home and ballads that the pedlars sold, and so my first two years with the Reades, before the war started, passed quite pleasantly, for I was but a child then, and my wants were few. The big house, however, Barton Manor, was burned to the ground during an early battle in the Civil War, and two of Sir Thomas's sons died during this skirmish, for they fought for King Charles-which was to say they fought for the losing side. When I think of our King Charles, he that was beheaded, I suddenly recall a bright memory that concerns that good man. On one particular day Lady Mary, Sir Thomas's wife, bade all the servants line up together in the great hall, saying she wished to speak to us on a matter of great importance. There were about twenty of us: cooks, housemaids, laundry maids, dairy maids, ostlers, footmen, butlers, and valets, and you can be sure that on that day we were all looking our neatest and best. Milady stood halfway up the stairs, where she could see everyone, and told us that two very important personages were coming to the house and everything had to be faultless for their visit. The house was to be seen at the peak of perfection, the evening meal was to consist of the rarest and most extravagant items, the musical entertainment to be the most delightful, the wines and sweetmeats the most delicious, and the whole household must work together to achieve this end. Every aspect of the house must be immaculate and we must fill our visitors with wonder, said Lady Mary. We must show them that even in remote Oxfordshire we are able to be hospitable. However, she went on to say, all this perfection had to be achieved as if by magic, for-apart from the waiting men who would serve the food-the servants were not to be seen going about their duties at any time. If we were seen, we would be dismissed in an instant. Why should that be? I asked one of the housemaids the following week as I flew between the innumerable jobs to be done before these feted guests arrived. Why are we not to be seen? It's not so much they must not see us, she said, but we who must not see them. Why then, who are they? You goose, she said, 'tis King Charles and Queen Henrietta who are coming. Did you not know that? I shook my head. But no one can know they are here, for there is money on their heads. I must have looked at her stupidly because she added, There's to be a war, haven't you heard? And it's to be called a civil war-that is, 'twill not be fought with France or Spain this time, but between ourselves and across our own lands. And the fight will be between those who are for the king, and those who are for parliament. And we are for the king? I asked. Of course! King Charles holds Sir Thomas as his friend and ally, and because of this the king and queen have chosen our house to say their goodbyes to each other before Queen Henrietta goes to France to sell her jewels. Why is she doing that? I had to ask, for I was as green as a sprout. To raise money for the king's cause, she said, and then lowered her voice. But there are spies everywhere and no one is supposed to know of their visit. And so the house was made ready. The tapestries were taken out, beaten, and re-hung, the wooden wainscoting hard-polished with beeswax, the portraits reglazed, the mirrors gilded. On the day of their coming, fires were lit in all the rooms, and the garden raided of its every flower so that great blossoming arrangements stood on each coffer and table. It was late afternoon when the king arrived, and I stood in my little room at the very top of the house, looking out across the drive. I remember thinking that if no one was supposed to know of his visit, then why had he arrived in a carriage and eight, for such an imposing retinue was almost unknown in Oxfordshire, and Sir Thomas himself only traveled in a carriage and four. The king's coach-what I could see of it from my window on high-was painted shiny red and purple and was very grand. The horses-all grays- wore matching red and purple ribbons in their manes and tails, and the coachmen were in purple livery. This retinue stopped at the marble-columned doorway, and when the king emerged from his carriage he stood for a few moments looking across at the knot garden, then stretched out his arms and yawned. I was surprised at this and strangely thrilled, for until then I'd not thought that kings were real people who might suffer cramps and tiredness, but were somehow above all that. I had even childishly supposed that a king and queen, being so important, would be larger than ordinary people, perhaps as big as giants. The king looked around him as if surveying the countryside over which he still had domain, and then gazed at the house and looked up . . . upwards . . . and saw me at my window staring at him in wonder. I waved to him and I think he smiled at me (I will always think so), and then Sir Thomas came down the steps of the house, bowed low, clasped his arm, and they disappeared inside. I did not see him again, but heard the musicians playing most of the night and, after his departure the next day, was given two sugared plums that had been left over from the banquet. I was very upset when he was beheaded last year, and sorry for his wife and poor children. It didn't seem at all proper to me that a king, God's chosen on Earth, should be put to death. I think many feel as I do, but we don't say so, for Cromwell has spies and the country is in his control now. Cromwell is not a bit like our tall and graceful king, who had elegant features and fine, curling hair and mustaches; Cromwell, they say, is short and stocky, with warts over his face, and I know I should be very frightened if I came face to face with him. But not as frightened as I am now. Excerpted from Newes From the Dead by Mary Hooper Copyright 2008 by Mary Hooper. Published in 2008 by Roaring Brook Press, A division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holding Limited Partnership. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. About the Author MARY HOOPER says, When I heard Anne Green's story on the car radio, I was absolutely captivated. I went straight home to find out more about her. What a story hers was: she gave birth in the most primitive conditions, then was thrown into a freezing, stinking prison and, later, sentenced to death. She said a said farewell to her family, climbed the scaffold, and then . . . what? Anne was 'dead' for several hours. Where did she go? I immersed myself in the facts, then sat down at my computer. I pictured her in her coffin; I felt I knew what she would want to say. My fingers began to fly across the keys . . . Mary Hooper has written more than 60 books for children and young adults, earning high praise as well as the North East Book Award for her YA novel, Megan. She has two grown children and lives with her husband Richard in Oxfordshire, England, the same area Anne Green came from. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. From AudioFile In mid-seventeenth-century England, Anne Green gives birth to a stillborn child. Thereafter, she is tried and sentenced to hang for infanticide. When her body is given to Oxford medical scholars for dissection, she is discovered to be still alive. The story unfolds in two parts--Anne's account of how she came to be hanged and the amazing medical miracle as told by a young Oxford scholar. Rosalyn Landor creates a wide variety of common voices for Anne's world and infuses her portrayal of Anne with appropriate innocence and bewilderment. Michael Page portrays the pomposity of the scholars, doing an especially fine job with the young, stammering Robert. The dual narration heightens the horror of this tale--based on a true story--making it a perfect choice for listening. S.G. AudioFile 2010, Portland, Maine --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. Review Intriguing and captivating.-Celia Rees A chilling, mesmerizing read.-Kirkus Reviews A grabber of a premise.-School Library Journal A historical mystery that is creepy in the best Edgar Allen Poe tradition, as well as thought-provoking.-Booklist First-rate . . . Anne's story, handled with skill and passion, will be hard for anyone to put down.-The Times (UK) A well researched, riveting read.-The Horn Book --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. From Booklist Newes from the Dead was the name ofa pamphlet that circulated in England in 1650 after a teenage housemaid,hanged for the crime of infanticide, awoke on the dissecting table. Hooper uses this case as the basis for a historical mystery that is creepyin the best Edgar Allen Poe tradition,as well asthought-provoking about sexual harassment and abuse. Thestory opens in a coffin, as the reader listens in on poor Anne's frantic coming-to-terms with where she is and how she got there: her days as a servant, her seduction by a young lord, the accusation of murder. Anne's thoughts, from coffin to dissecting table, are juxtaposed with a third-person narrative, centering ona nervous young surgeon who is on hand to witness and assist in the young woman's dissection. Hooperexplains that surgeonswere allowed to conduct autopsies on criminals, and it's just such intriguing tidbits of Cromwellian historythat add heft tothis suspenseful novel.Give this to readers who prefer theirhistorical mysteries straight up--without an overlay of fantasy. Grades 9-12. --Connie Fletcher --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

Publication Details

Title:

Author(s):

Illustrator:

Binding: Paperback

Published by: Definitions: , 2009

Edition:

ISBN: 9781862303638 | 1862303630

326 pages.

Book Condition: Very Good

Pickup currently unavailable at Book Express Warehouse

Product information

New Zealand Delivery

Shipping Options

Shipping options are shown at checkout and will vary depending on the delivery address and weight of the books.

We endeavour to ship the following day after your order is made and to have pick up orders available the same day. We ship Monday-Friday. Any orders made on a Friday afternoon will be sent the following Monday. We are unable to deliver on Saturday and Sunday.

Pick Up is Available in NZ:

Warehouse Pick Up Hours

- Monday - Friday: 9am-5pm

- 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon NZ

Please make sure we have confirmed your order is ready for pickup and bring your confirmation email with you.

Rates

-

New Zealand Standard Shipping - $6.00

- New Zealand Standard Rural Shipping - $10.00

- Free Nationwide Standard Shipping on all Orders $75+

Please allow up to 5 working days for your order to arrive within New Zealand before contacting us about a late delivery. We use NZ Post and the tracking details will be emailed to you as soon as they become available. There may be some courier delays that are out of our control.

International Delivery

We currently ship to Australia and a range of international locations including: Belgium, Canada, China, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, United States, Hong Kong SAR, Thailand, Philippines, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden & Singapore. If your country is not listed, we may not be able to ship to you, or may only offer a quoting shipping option, please contact us if you are unsure.

International orders normally arrive within 2-4 weeks of shipping. Please note that these orders need to pass through the customs office in your country before it will be released for final delivery, which can occasionally cause additional delays. Once an order leaves our warehouse, carrier shipping delays may occur due to factors outside our control. We, unfortunately, can’t control how quickly an order arrives once it has left our warehouse. Contacting the carrier is the best way to get more insight into your package’s location and estimated delivery date.

- Global Standard 1 Book Rate: $37 + $10 for every extra book up to 20kg

- Australia Standard 1 Book Rate: $14 + $4 for every extra book

Any parcels with a combined weight of over 20kg will not process automatically on the website and you will need to contact us for a quote.

Payment Options

On checkout you can either opt to pay by credit card (Visa, Mastercard or American Express), Google Pay, Apple Pay, Shop Pay & Union Pay. Paypal, Afterpay and Bank Deposit.

Transactions are processed immediately and in most cases your order will be shipped the next working day. We do not deliver weekends sorry.

If you do need to contact us about an order please do so here.

You can also check your order by logging in.

Contact Details

- Trade Name: Book Express Ltd

- Phone Number: (+64) 22 852 6879

- Email: sales@bookexpress.co.nz

- Address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, 4821, New Zealand.

- GST Number: 103320957 - We are registered for GST in New Zealand

- NZBN: 9429031911290

We have a 30-day return policy, which means you have 30 days after receiving your item to request a return.

To be eligible for a return, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unread.

To start a return, you can contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz. Please note that returns will need to be sent to the following address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, New Zealand 4821.

If your return is for a quality or incorrect item, the cost of return will be on us, and will refund your cost. If it is for a change of mind, the return will be at your cost.

You can always contact us for any return question at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.

Damages and issues

Please inspect your order upon reception and contact us immediately if the item is defective, damaged or if you receive the wrong item, so that we can evaluate the issue and make it right.

Exceptions / non-returnable items

Certain types of items cannot be returned, like perishable goods (such as food, flowers, or plants), custom products (such as special orders or personalised items), and personal care goods (such as beauty products). Although we don't currently sell anything like this. Please get in touch if you have questions or concerns about your specific item.

Unfortunately, we cannot accept returns on gift cards.

Exchanges

The fastest way to ensure you get what you want is to return the item you have, and once the return is accepted, make a separate purchase for the new item.

European Union 14 day cooling off period

Notwithstanding the above, if the merchandise is being shipped into the European Union, you have the right to cancel or return your order within 14 days, for any reason and without a justification. As above, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. You’ll also need the receipt or proof of purchase.

Refunds

We will notify you once we’ve received and inspected your return, and let you know if the refund was approved or not. If approved, you’ll be automatically refunded on your original payment method within 10 business days. Please remember it can take some time for your bank or credit card company to process and post the refund too.

If more than 15 business days have passed since we’ve approved your return, please contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.