Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, Revised and Expanded Edition by Oliver Sacks

Revised and Expanded With the same trademark compassion and erudition he brought to The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Oliver Sacks explores the place music occupies in the brain and how it affects the human condition. In Musicophilia, he shows us a variety of what he calls musical misalignments. Among them: a man struck by lightning who suddenly desires to become a pianist at the age of forty-two; an entire group of children with Williams syndrome, who are hypermusical from birth; people with amusia, to whom a symphony sounds like the clattering of pots and pans; and a man whose memory spans only seven seconds-for everything but music. Illuminating, inspiring, and utterly unforgettable, Musicophilia is Oliver Sacks' latest masterpiece. Editorial Reviews Review Powerful and compassionate. . . . A book that not only contributes to our understanding of the elusive magic of music but also illuminates the strange workings, and misfirings, of the human mind. -The New York TimesCurious, cultured, caring. . . . Musicophilia allows readers to join Sacks where he is most alive, amid melodies and with his patients. -The Washington Post Book WorldSacks has an expert bedside manner: informed but humble, self-questioning, literary without being self-conscious.-Los Angeles TimesSacks spins one fascinating tale after another to show what happens when music and the brain mix it up. -NewsweekSacks once again examines the many mysteries of a fascinating subject. -The Seattle Times About the Author Oliver Sacks was a physician, writer, and professor of neurology. Born in London in 1933, he moved to New York City in 1965, where he launched his medical career and began writing case studies of his patients. Called the poet laureate of medicine by The New York Times, Sacks is the author of more than a dozen books, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia, and Awakenings, which inspired an Oscar-nominated film and a play by Harold Pinter. He was the recipient of many awards and honorary degrees, and was made a Commander of the British Empire in 2008 for services to medicine. He died in 2015. www.oliversacks Excerpt. ® Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. A Bolt from the Blue: Sudden MusicophiliaTony Cicoria was forty-two, very fit and robust, a former college football player who had become a well-regarded orthopedic surgeon in a small city in upstate New York. He was at a lakeside pavilion for a family gathering one fall afternoon. It was pleasant and breezy, but he noticed a few storm clouds in the distance; it looked like rain.He went to a pay phone outside the pavilion to make a quick call to his mother (this was in 1994, before the age of cell phones). He still remembers every single second of what happened next: I was talking to my mother on the phone. There was a little bit of rain, thunder in the distance. My mother hung up. The phone was a foot away from where I was standing when I got struck. I remember a flash of light coming out of the phone. It hit me in the face. Next thing I remember, I was flying backwards.Then-he seemed to hesitate before telling me this-I was flying forwards. Bewildered. I looked around. I saw my own body on the ground. I said to myself, 'Oh shit, I'm dead.' I saw people converging on the body. I saw a woman-she had been standing waiting to use the phone right behind me-position herself over my body, give it CPR. . . . I floated up the stairs-my consciousness came with me. I saw my kids, had the realization that they would be okay. Then I was surrounded by a bluish-white light . . . an enormous feeling of well-being and peace. The highest and lowest points of my life raced by me. No emotion associated with these . . . pure thought, pure ecstasy. I had the perception of accelerating, being drawn up . . . there was speed and direction. Then, as I was saying to myself, 'This is the most glorious feeling I have ever had'-SLAM! I was back.Dr. Cicoria knew he was back in his own body because he had pain-pain from the burns on his face and his left foot, where the electrical charge had entered and exited his body-and, he realized, only bodies have pain. He wanted to go back, he wanted to tell the woman to stop giving him CPR, to let him go; but it was too late-he was firmly back among the living. After a minute or two, when he could speak, he said, It's okay-I'm a doctor! The woman (she turned out to be an intensive-care-unit nurse) replied, A few minutes ago, you weren't.The police came and wanted to call an ambulance, but Cicoria refused, delirious. They took him home instead (it seemed to take hours), where he called his own doctor, a cardiologist. The cardiologist, when he saw him, thought Cicoria must have had a brief cardiac arrest, but could find nothing amiss with examination or EKG. With these things, you're alive or dead, the cardiologist remarked. He did not feel that Dr. Cicoria would suffer any further consequences of this bizarre accident.Cicoria also consulted a neurologist-he was feeling sluggish (most unusual for him) and having some difficulties with his memory. He found himself forgetting the names of people he knew well. He was examined neurologically, had an EEG and an MRI. Again, nothing seemed amiss.A couple of weeks later, when his energy returned, Dr. Cicoria went back to work. There were still some lingering memory problems-he occasionally forgot the names of rare diseases or surgical procedures-but all his surgical skills were unimpaired. In another two weeks, his memory problems disappeared, and that, he thought, was the end of the matter.What then happened still fills Cicoria with amazement, even now, a dozen years later. Life had returned to normal, seemingly, when suddenly, over two or three days, there was this insatiable desire to listen to piano music. This was completely out of keeping with anything in his past. He had had a few piano lessons as a boy, he said, but no real interest. He did not have a piano in his house. What music he did listen to tended to be rock music.With this sudden onset of craving for piano music, he began to buy recordings and became especially enamored of a Vladimir Ashkenazy recording of Chopin favorites-the Military Polonaise, the Winter Wind Étude, the Black Key Étude, the A-flat Polonaise, the B-flat Minor Scherzo. I loved them all, Tony said. I had the desire to play them. I ordered all the sheet music. At this point, one of our babysitters asked if she could store her piano in our house-so now, just when I craved one, a piano arrived, a nice little upright. It suited me fine. I could hardly read the music, could barely play, but I started to teach myself. It had been more than thirty years since the few piano lessons of his boyhood, and his fingers seemed stiff and awkward.And then, on the heels of this sudden desire for piano music, Cicoria started to hear music in his head. The first time, he said, it was in a dream. I was in a tux, onstage; I was playing something I had written. I woke up, startled, and the music was still in my head. I jumped out of bed, started trying to write down as much of it as I could remember. But I hardly knew how to notate what I heard. This was not too successful-he had never tried to write or notate music before. But whenever he sat down at the piano to work on the Chopin, his own music would come and take me over. It had a very powerful presence.I was not quite sure what to make of this peremptory music, which would intrude almost irresistibly and overwhelm him. Was he having musical hallucinations? No, Dr. Cicoria said, they were not hallucinations-inspiration was a more apt word. The music was there, deep inside him-or somewhere-and all he had to do was let it come to him. It's like a frequency, a radio band. If I open myself up, it comes. I want to say, 'It comes from heaven,' as Mozart said.His music is ceaseless. It never runs dry, he continued. If anything, I have to turn it off.Now he had to wrestle not just with learning to play the Chopin, but to give form to the music continually running in his head, to try it out on the piano, to get it on manuscript paper. It was a terrible struggle, he said. I would get up at four in the morning and play till I went to work, and when I got home from work I was at the piano all evening. My wife was not really pleased. I was possessed.In the third month after being struck by lightning, then, Cicoria-once an easygoing, genial family man, almost indifferent to music-was inspired, even possessed, by music, and scarcely had time for anything else. It began to dawn on him that perhaps he had been saved for a special reason. I came to think, he said, that the only reason I had been allowed to survive was the music. I asked him whether he had been a religious man before the lightning. He had been raised Catholic, he said, but had never been particularly observant; he had some unorthodox beliefs, too, such as in reincarnation.He himself, he grew to think, had had a sort of reincarnation, had been transformed and given a special gift, a mission, to tune in to the music that he called, half metaphorically, the music from heaven. This came, often, in an absolute torrent of notes with no breaks, no rests, between them, and he would have to give it shape and form. (As he said this, I thought of Caedmon, the seventh-century Anglo-Saxon poet, an illiterate goatherd who, it was said, had received the art of song in a dream one night, and spent the rest of his life praising God and creation in hymns and poems.)Cicoria continued to work on his piano playing and his compositions. He got books on notation, and soon realized that he needed a music teacher. He would travel to concerts by his favorite performers but had nothing to do with musical friends in his own town or musical activities there. This was a solitary pursuit, between himself and his muse.I asked whether he had experienced other changes since the lightning strike-a new appreciation of art, perhaps, different taste in reading, new beliefs? Cicoria said he had become very spiritual since his near-death experience. He had started to read every book he could find about near-death experiences and about lightning strikes. And he had got a whole library on Tesla, as well as anything on the terrible and beautiful power of high-voltage electricity. He felt he could sometimes see auras of light or energy around people's bodies-he had never seen this before the lightning bolt.Some years passed, and Cicoria's new life, his inspiration, never deserted him for a moment. He continued to work full-time as a surgeon, but his heart and mind now centered on music. He got divorced in 2004, and the same year had a fearful motorcycle accident. He had no memory of this, but his Harley was struck by another vehicle, and he was found in a ditch, unconscious and badly injured, with broken bones, a ruptured spleen, a perforated lung, cardiac contusions, and, despite his helmet, head injuries. In spite of all this, he made a complete recovery and was back at work in two months. Neither the accident nor his head injury nor his divorce seemed to have made any difference to his passion for playing and composing music.I have never met another person with a story like Tony Cicoria's, but I have occasionally had patients with a similar sudden onset of musical or artistic interests-including Salimah M., a research chemist. In her early forties, Salimah started to have brief periods, lasting a minute or less, in which she would get a strange feeling-sometimes a sense that she was on a beach that she had once known, while at the same time being perfectly conscious of her current surroundings and able to continue a conversation, or drive a car, or do whatever she had been doing. Occasionally these episodes were accompanied by a sour taste in the mouth. She noticed these strange occurrences, but did not think of them as having any neurological significance. It was only when she had a grand mal seizure in the summer of 2003 that she went to a neurologist and was given brain scans, which revealed a large tumor in her right temporal lobe. This had been the cause of her strange episodes, which were now realized to be temporal lobe seizures. The tumor, her doctors felt, was malignant (though it was probably an oligodendroglioma, of relatively low malignancy) and needed to be removed. Salimah wondered if she had been given a death sentence and was fearful of the operation and its possible consequences; she and her husband had been told that there might be some personality changes following it. But in the event, the surgery went well, most of the tumor was removed, and after a period of convalescence, Salimah was able to return to her work as a chemist.She had been a fairly reserved woman before the surgery, who would occasionally be annoyed or preoccupied by small things like dust or untidiness; her husband said she was sometimes obsessive about jobs that needed to be done around the house. But now, after the surgery, Salimah seemed unperturbed by such domestic matters. She had become, in the idiosyncratic words of her husband (English was not their first language), a happy cat. She was, he declared, a joyologist.Salimah's new cheerfulness was apparent at work. She had worked in the same laboratory for fifteen years and had always been admired for her intelligence and dedication. But now, while losing none of this professional competence, she seemed a much warmer person, keenly sympathetic and interested in the lives and feelings of her co-workers. Where before, in a colleague's words, she had been much more into herself, she now became the confidante and social center of the entire lab.At home, too, she shed some of her Marie Curie-like, work-oriented personality. She permitted herself time off from her thinking, her equations, and became more interested in going to movies or parties, living it up a bit. And a new love, a new passion, entered her life. She had been vaguely musical, in her own words, as a girl, had played the piano a little, but music had never played any great part in her life. Now it was different. She longed to hear music, to go to concerts, to listen to classical music on the radio or on CDs. She could be moved to rapture or tears by music which had carried no special feeling for her before. She became addicted to her car radio, which she would listen to while driving to work. A colleague who happened to pass her on the road to the lab said that the music on her radio was incredibly loud-he could hear it a quarter of a mile away. Salimah, in her convertible, was entertaining the whole freeway.Like Tony Cicoria, Salimah showed a drastic transformation from being only vaguely interested in music to being passionately excited by music and in continual need of it. And with both of them, there were other, more general changes, too-a surge of emotionality, as if emotions of every sort were being stimulated or released. In Salimah's words, What happened after the surgery-I felt reborn. That changed my outlook on life and made me appreciate every minute of it. Excerpt. ® Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. A Bolt from the Blue: Sudden MusicophiliaTony Cicoria was forty-two, very fit and robust, a former college football player who had become a well-regarded orthopedic surgeon in a small city in upstate New York. He was at a lakeside pavilion for a family gathering one fall afternoon. It was pleasant and breezy, but he noticed a few storm clouds in the distance; it looked like rain.He went to a pay phone outside the pavilion to make a quick call to his mother (this was in 1994, before the age of cell phones). He still remembers every single second of what happened next: I was talking to my mother on the phone. There was a little bit of rain, thunder in the distance. My mother hung up. The phone was a foot away from where I was standing when I got struck. I remember a flash of light coming out of the phone. It hit me in the face. Next thing I remember, I was flying backwards.Then-he seemed to hesitate before telling me this-I was flying forwards. Bewildered. I looked around. I saw my own body on the ground. I said to myself, 'Oh shit, I'm dead.' I saw people converging on the body. I saw a woman-she had been standing waiting to use the phone right behind me-position herself over my body, give it CPR. . . . I floated up the stairs-my consciousness came with me. I saw my kids, had the realization that they would be okay. Then I was surrounded by a bluish-white light . . . an enormous feeling of well-being and peace. The highest and lowest points of my life raced by me. No emotion associated with these . . . pure thought, pure ecstasy. I had the perception of accelerating, being drawn up . . . there was speed and direction. Then, as I was saying to myself, 'This is the most glorious feeling I have ever had'-SLAM! I was back.Dr. Cicoria knew he was back in his own body because he had pain-pain from the burns on his face and his left foot, where the electrical charge had entered and exited his body-and, he realized, only bodies have pain. He wanted to go back, he wanted to tell the woman to stop giving him CPR, to let him go; but it was too late-he was firmly back among the living. After a minute or two, when he could speak, he said, It's okay-I'm a doctor! The woman (she turned out to be an intensive-care-unit nurse) replied, A few minutes ago, you weren't.The police came and wanted to call an ambulance, but Cicoria refused, delirious. They took him home instead (it seemed to take hours), where he called his own doctor, a cardiologist. The cardiologist, when he saw him, thought Cicoria must have had a brief cardiac arrest, but could find nothing amiss with examination or EKG. With these things, you're alive or dead, the cardiologist remarked. He did not feel that Dr. Cicoria would suffer any further consequences of this bizarre accident.Cicoria also consulted a neurologist-he was feeling sluggish (most unusual for him) and having some difficulties with his memory. He found himself forgetting the names of people he knew well. He was examined neurologically, had an EEG and an MRI. Again, nothing seemed amiss.A couple of weeks later, when his energy returned, Dr. Cicoria went back to work. There were still some lingering memory problems-he occasionally forgot the names of rare diseases or surgical procedures-but all his surgical skills were unimpaired. In another two weeks, his memory problems disappeared, and that, he thought, was the end of the matter.What then happened still fills Cicoria with amazement, even now, a dozen years later. Life had returned to normal, seemingly, when suddenly, over two or three days, there was this insatiable desire to listen to piano music. This was completely out of keeping with anything in his past. He had had a few piano lessons as a boy, he said, but no real interest. He did not have a piano in his house. What music he did listen to tended to be rock music.With this sudden onset of craving for piano music, he began to buy recordings and became especially enamored of a Vladimir Ashkenazy recording of Chopin favorites-the Military Polonaise, the Winter Wind Étude, the Black Key Étude, the A-flat Polonaise, the B-flat Minor Scherzo. I loved them all, Tony said. I had the desire to play them. I ordered all the sheet music. At this point, one of our babysitters asked if she could store her piano in our house-so now, just when I craved one, a piano arrived, a nice little upright. It suited me fine. I could hardly read the music, could barely play, but I started to teach myself. It had been more than thirty years since the few piano lessons of his boyhood, and his fingers seemed stiff and awkward.And then, on the heels of this sudden desire for piano music, Cicoria started to hear music in his head. The first time, he said, it was in a dream. I was in a tux, onstage; I was playing something I had written. I woke up, startled, and the music was still in my head. I jumped out of bed, started trying to write down as much of it as I could remember. But I hardly knew how to notate what I heard. This was not too successful-he had never tried to write or notate music before. But whenever he sat down at the piano to work on the Chopin, his own music would come and take me over. It had a very powerful presence.I was not quite sure what to make of this peremptory music, which would intrude almost irresistibly and overwhelm him. Was he having musical hallucinations? No, Dr. Cicoria said, they were not hallucinations-inspiration was a more apt word. The music was there, deep inside him-or somewhere-and all he had to do was let it come to him. It's like a frequency, a radio band. If I open myself up, it comes. I want to say, 'It comes from heaven,' as Mozart said.His music is ceaseless. It never runs dry, he continued. If anything, I have to turn it off.Now he had to wrestle not just with learning to play the Chopin, but to give form to the music continually running in his head, to try it out on the piano, to get it on manuscript paper. It was a terrible struggle, he said. I would get up at four in the morning and play till I went to work, and when I got home from work I was at the piano all evening. My wife was not really pleased. I was possessed.In the third month after being struck by lightning, then, Cicoria-once an easygoing, genial family man, almost indifferent to music-was inspired, even possessed, by music, and scarcely had time for anything else. It began to dawn on him that perhaps he had been saved for a special reason. I came to think, he said, that the only reason I had been allowed to survive was the music. I asked him whether he had been a religious man before the lightning. He had been raised Catholic, he said, but had never been particularly observant; he had some unorthodox beliefs, too, such as in reincarnation.He himself, he grew to think, had had a sort of reincarnation, had been transformed and given a special gift, a mission, to tune in to the music that he called, half metaphorically, the music from heaven. This came, often, in an absolute torrent of notes with no breaks, no rests, between them, and he would have to give it shape and form. (As he said this, I thought of Caedmon, the seventh-century Anglo-Saxon poet, an illiterate goatherd who, it was said, had received the art of song in a dream one night, and spent the rest of his life praising God and creation in hymns and poems.)Cicoria continued to work on his piano playing and his compositions. He got books on notation, and soon realized that he needed a music teacher. He would travel to concerts by his favorite performers but had nothing to do with musical friends in his own town or musical activities there. This was a solitary pursuit, between himself and his muse.I asked whether he had experienced other changes since the lightning strike-a new appreciation of art, perhaps, different taste in reading, new beliefs? Cicoria said he had become very spiritual since his near-death experience. He had started to read every book he could find about near-death experiences and about lightning strikes. And he had got a whole library on Tesla, as well as anything on the terrible and beautiful power of high-voltage electricity. He felt he could sometimes see auras of light or energy around people's bodies-he had never seen this before the lightning bolt.Some years passed, and Cicoria's new life, his inspiration, never deserted him for a moment. He continued to work full-time as a surgeon, but his heart and mind now centered on music. He got divorced in 2004, and the same year had a fearful motorcycle accident. He had no memory of this, but his Harley was struck by another vehicle, and he was found in a ditch, unconscious and badly injured, with broken bones, a ruptured spleen, a perforated lung, cardiac contusions, and, despite his helmet, head injuries. In spite of all this, he made a complete recovery and was back at work in two months. Neither the accident nor his head injury nor his divorce seemed to have made any difference to his passion for playing and composing music.I have never met another person with a story like Tony Cicoria's, but I have occasionally had patients with a similar sudden onset of musical or artistic interests-including Salimah M., a research chemist. In her early forties, Salimah started to have brief periods, lasting a minute or less, in which she would get a strange feeling-sometimes a sense that she was on a beach that she had once known, while at the same time being perfectly conscious of her current surroundings and able to continue a conversation, or drive a car, or do whatever she had been doing. Occasionally these episodes were accompanied by a sour taste in the mouth. She noticed these strange occurrences, but did not think of them as having any neurological significance. It was only when she had a grand mal seizure in the summer of 2003 that she went to a neurologist and was given brain scans, which revealed a large tumor in her right temporal lobe. This had been the cause of her strange episodes, which were now realized to be temporal lobe seizures. The tumor, her doctors felt, was malignant (though it was probably an oligodendroglioma, of relatively low malignancy) and needed to be removed. Salimah wondered if she had been given a death sentence and was fearful of the operation and its possible consequences; she and her husband had been told that there might be some personality changes following it. But in the event, the surgery went well, most of the tumor was removed, and after a period of convalescence, Salimah was able to return to her work as a chemist.She had been a fairly reserved woman before the surgery, who would occasionally be annoyed or preoccupied by small things like dust or untidiness; her husband said she was sometimes obsessive about jobs that needed to be done around the house. But now, after the surgery, Salimah seemed unperturbed by such domestic matters. She had become, in the idiosyncratic words of her husband (English was not their first language), a happy cat. She was, he declared, a joyologist.Salimah's new cheerfulness was apparent at work. She had worked in the same laboratory for fifteen years and had always been admired for her intelligence and dedication. But now, while losing none of this professional competence, she seemed a much warmer person, keenly sympathetic and interested in the lives and feelings of her co-workers. Where before, in a colleague's words, she had been much more into herself, she now became the confidante and social center of the entire lab.At home, too, she shed some of her Marie Curie-like, work-oriented personality. She permitted herself time off from her thinking, her equations, and became more interested in going to movies or parties, living it up a bit. And a new love, a new passion, entered her life. She had been vaguely musical, in her own words, as a girl, had played the piano a little, but music had never played any great part in her life. Now it was different. She longed to hear music, to go to concerts, to listen to classical music on the radio or on CDs. She could be moved to rapture or tears by music which had carried no special feeling for her before. She became addicted to her car radio, which she would listen to while driving to work. A colleague who happened to pass her on the road to the lab said that the music on her radio was incredibly loud-he could hear it a quarter of a mile away. Salimah, in her convertible, was entertaining the whole freeway.Like Tony Cicoria, Salimah showed a drastic transformation from being only vaguely interested in music to being passionately excited by music and in continual need of it. And with both of them, there were other, more general changes, too-a surge of emotionality, as if emotions of every sort were being stimulated or released. In Salimah's words, What happened after the surgery-I felt reborn. That changed my outlook on life and made me appreciate every minute of it.

Publication Details

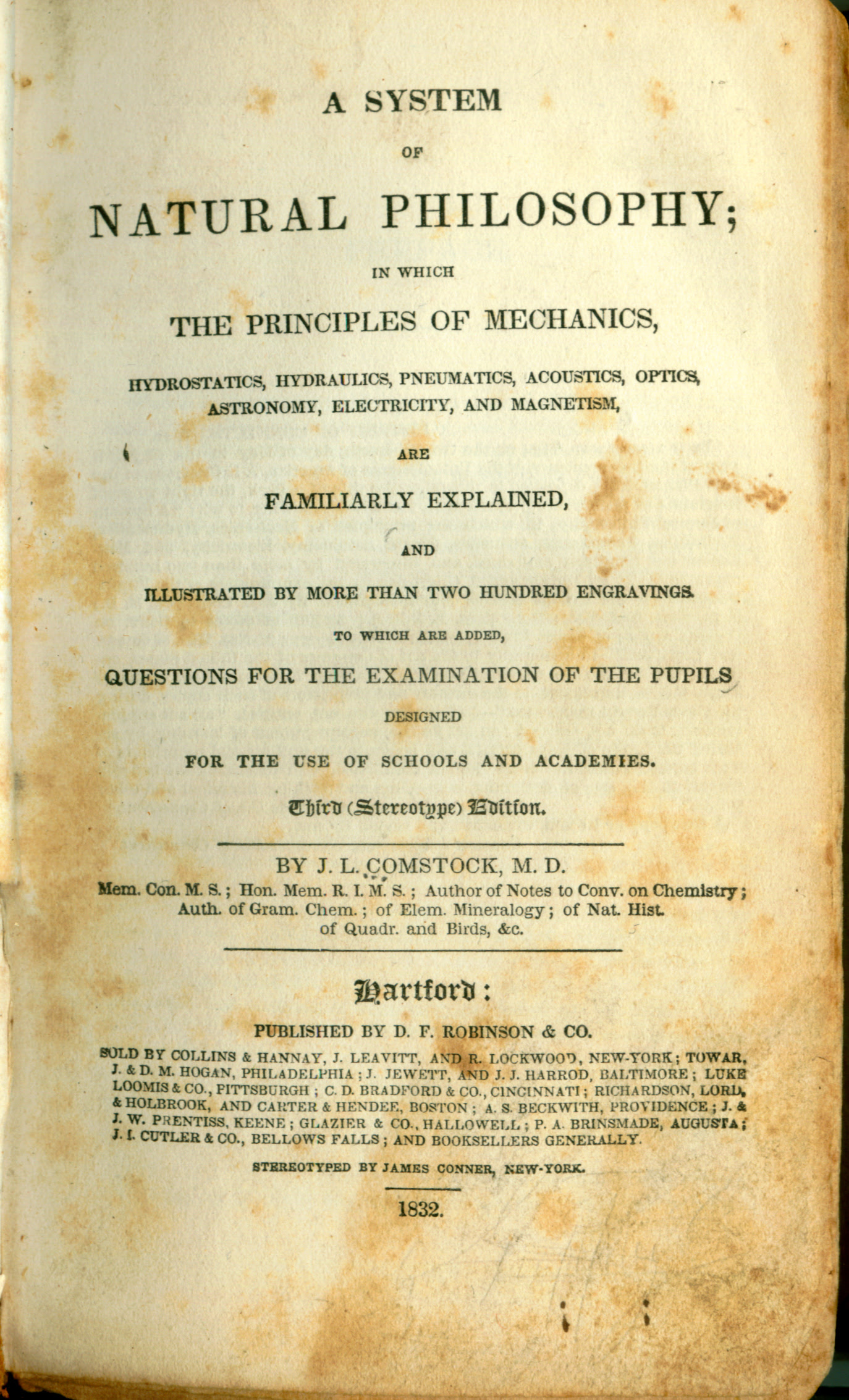

Title:

Author(s):

Illustrator:

Binding: Paperback

Published by: Vintage: , 2008

Edition:

ISBN: 9781400033539 | 1400033535

425 pages.

Book Condition: Very Good

Pickup currently unavailable at Book Express Warehouse

Product information

New Zealand Delivery

Shipping Options

Shipping options are shown at checkout and will vary depending on the delivery address and weight of the books.

We endeavour to ship the following day after your order is made and to have pick up orders available the same day. We ship Monday-Friday. Any orders made on a Friday afternoon will be sent the following Monday. We are unable to deliver on Saturday and Sunday.

Pick Up is Available in NZ:

Warehouse Pick Up Hours

- Monday - Friday: 9am-5pm

- 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon NZ

Please make sure we have confirmed your order is ready for pickup and bring your confirmation email with you.

Rates

-

New Zealand Standard Shipping - $6.00

- New Zealand Standard Rural Shipping - $10.00

- Free Nationwide Standard Shipping on all Orders $75+

Please allow up to 5 working days for your order to arrive within New Zealand before contacting us about a late delivery. We use NZ Post and the tracking details will be emailed to you as soon as they become available. There may be some courier delays that are out of our control.

International Delivery

We currently ship to Australia and a range of international locations including: Belgium, Canada, China, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, United States, Hong Kong SAR, Thailand, Philippines, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden & Singapore. If your country is not listed, we may not be able to ship to you, or may only offer a quoting shipping option, please contact us if you are unsure.

International orders normally arrive within 2-4 weeks of shipping. Please note that these orders need to pass through the customs office in your country before it will be released for final delivery, which can occasionally cause additional delays. Once an order leaves our warehouse, carrier shipping delays may occur due to factors outside our control. We, unfortunately, can’t control how quickly an order arrives once it has left our warehouse. Contacting the carrier is the best way to get more insight into your package’s location and estimated delivery date.

- Global Standard 1 Book Rate: $37 + $10 for every extra book up to 20kg

- Australia Standard 1 Book Rate: $14 + $4 for every extra book

Any parcels with a combined weight of over 20kg will not process automatically on the website and you will need to contact us for a quote.

Payment Options

On checkout you can either opt to pay by credit card (Visa, Mastercard or American Express), Google Pay, Apple Pay, Shop Pay & Union Pay. Paypal, Afterpay and Bank Deposit.

Transactions are processed immediately and in most cases your order will be shipped the next working day. We do not deliver weekends sorry.

If you do need to contact us about an order please do so here.

You can also check your order by logging in.

Contact Details

- Trade Name: Book Express Ltd

- Phone Number: (+64) 22 852 6879

- Email: sales@bookexpress.co.nz

- Address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, 4821, New Zealand.

- GST Number: 103320957 - We are registered for GST in New Zealand

- NZBN: 9429031911290

We have a 30-day return policy, which means you have 30 days after receiving your item to request a return.

To be eligible for a return, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unread.

To start a return, you can contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz. Please note that returns will need to be sent to the following address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, New Zealand 4821.

If your return is for a quality or incorrect item, the cost of return will be on us, and will refund your cost. If it is for a change of mind, the return will be at your cost.

You can always contact us for any return question at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.

Damages and issues

Please inspect your order upon reception and contact us immediately if the item is defective, damaged or if you receive the wrong item, so that we can evaluate the issue and make it right.

Exceptions / non-returnable items

Certain types of items cannot be returned, like perishable goods (such as food, flowers, or plants), custom products (such as special orders or personalised items), and personal care goods (such as beauty products). Although we don't currently sell anything like this. Please get in touch if you have questions or concerns about your specific item.

Unfortunately, we cannot accept returns on gift cards.

Exchanges

The fastest way to ensure you get what you want is to return the item you have, and once the return is accepted, make a separate purchase for the new item.

European Union 14 day cooling off period

Notwithstanding the above, if the merchandise is being shipped into the European Union, you have the right to cancel or return your order within 14 days, for any reason and without a justification. As above, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. You’ll also need the receipt or proof of purchase.

Refunds

We will notify you once we’ve received and inspected your return, and let you know if the refund was approved or not. If approved, you’ll be automatically refunded on your original payment method within 10 business days. Please remember it can take some time for your bank or credit card company to process and post the refund too.

If more than 15 business days have passed since we’ve approved your return, please contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.