Human Traces by Sebastian Faulks

What is it to be human? This question, as in Birdsong, is at the heart of Human Traces. The story begins in Brittany where a young, poor boy somehow passes his medical exams and goes to Paris, where he attends the lectures of Charcot, the Parisian neurologist who set the world on its head in the 1870s. With a friend, he sets up a clinic in the mysterious mountain district of Carinthia in south-east Austria. If The Girl at the Lion d'Or was a simple three-movement symphony, Birdsong an opera, Charlotte Gray a complex four-movement symphony and On Green Dolphin Street a concerto, then Human Traces is a Wagnerian grand opera. From the Hardcover edition. Editorial Reviews Review Faulks is beyond doubt a master. -Financial Times One of the most impressive novelists of his generation. -Sunday Telegraph From the Hardcover edition. About the Author Sebastian Faulks is best known for his French trilogy, The Girl at the Lion d'Or, Birdsong and Charlotte Gray. He has also worked extensively as a journalist. From the Hardcover edition. Excerpt. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. I An evening mist, salted by the western sea, was gathering on the low hills - reed-spattered rises running up from the rocks then back into the gorse- and bracken-covered country - and on to the roads that joined the villages, where lamps and candles flickered behind the shutters of the grey stone houses. It was poor country - so poor, remarked the Curé, who had recently arrived from Angers, that the stones of the shore called out for God's mercy. With the mist came sputtering rain, made invisible by the extinguished light, as it exploded like flung gravel at the windows, while stronger gusts made the shivering pine trees shed their needles on the dark, sanded earth. Jacques Rebière listened to the sounds from outside as he looked through the window of his bedroom; for a moment, a dim moon allowed him to see clouds foaming in the darkness. The weather reminded him, often, that it was not just he, at sixteen years old, who was young, but all mankind: a species that took infant steps on the drifts and faults of the earth. Between the ends of his dirtied fingers, Jacques held a small blade which, over the course of several days, he had whetted to surgical sharpness. He pulled a candle closer. From downstairs he could hear the sound of his father's voice in reluctant negotiation. The house was at the top of a narrow street that ran off the main square of Sainte Agnès. Behind it, the village ended and there were thick woods - Monsieur Rebière's own property - where Jacques was meant to trap birds and rabbits and prevent other villagers doing likewise. The garden had an orchard of pear and apple trees whose fruits were collected and set to keep in one of the outbuildings. Rebière's was a house of many stores: of sheds with beaten earth underfoot and slatted wooden shelves; of brick-floored cellars with stone bins on which the cobwebs closed the access to the bottles; of barred pantry and latched larder with shelves of nuts and preserved fruits. The keys were on a ring in the pocket of Rebière's waistcoat. Although born no more than sixty years earlier, he was known as 'old Rebière', perhaps for the arthritic movement of his knees, when he heaved himself up from his chair and straightened the joints beneath his breeches. He preferred to do business standing up; it gave the transaction a temporary air, helping to convince the other party that bargaining time was short. Old Rebière was a forester who worked as the agent for a landowner from Lorient. Over the years he had done some business on his own account, acquiring some parcels of land, three cottages that the heirs did not want to keep, some fields and woodland. Most of his work was no more than that of bailiff or rent collector, but he liked to try to negotiate private deals with a view to becoming a businessman in his own right. Born in the year after Waterloo, he had lived under a republic, three kings and an emperor; twice mayor of the local town, he had found it made little difference which government was in Paris, since so few edicts devolved from the distant centre to his own Breton world. The parlour of the house had smoke-stained wooden panelling and a white stone chimneypiece decorated with the carved head of a wild boar. A small fire was smouldering in the grate as Rebière attempted to conclude his meeting with the notary who had come to see him. He never invited guests into his study but preferred to speak to them in this public room, as though he might later need witnesses to what had passed between them. His second wife sat in her accustomed chair by the door, sewing and listening. Rebière's tactic was to say as little as possible; he had found that silence, accompanied by pained inhalation, often induced nervousness in the other side. His contributions, when they were unavoidable, were delivered in a reluctant murmur, melancholy, full of a weariness at a world that had obliged him to agree terms so self-wounding. 'I am not a peasant,' he told his son. 'I am not one of those men you see portrayed at the theatre in Paris, who buries his gold in a sock and never buys a bonnet for his wife. I am a businessman who understands the modern world.' From upstairs, Jacques could still hear his father's business murmur. It was true that he was not a peasant, though his parents had been; true too, that he was not the miser of the popular imagination, though partly because the amount of gold he had to hoard was not great enough: forty years of dealing had brought him a modest return, and perhaps, thought Jacques, this was why his father had forbidden him to study any further. From the age of thirteen, he had been set to work, looking after the properties, mending roofs and fences, clearing trees while his father travelled to Quimper and Vannes to cultivate new acquaintances. Jacques looked back to his table, not wanting to waste the light of the wax candle he had begged from Tante Mathilde in place of the dingy ox-tallow which was all his father would allow him. He took the blade and began, very carefully, to make a shallow incision in the neck of a frog he had pinned, through its splayed feet, to the untreated wood. He had never attempted the operation before and was anxious not to damage what lay beneath the green skin, moist from the saline in which he had kept it. The frog was on its front, and Jacques's blade travelled smoothly up over the top of its head and stopped between the bulging eyes. He then cut two semicircular flaps to join at the nape of the neck and pushed back the pouches of peeled skin, with their pearls of eyes. Beneath his delicate touch he could see now that there was little in the way of protection for the exposed brain. He took out a magnifying glass. What is a frog's fury? he thought, as he gazed at the tiny thinking organ his knife had exposed. It was beautiful. What does it feel for its spawn or its mate or the flash of water over its skin? The brain of an amphibian is a poor thing, the Curé had warned him; he promised that soon he would acquire the head of a cow from the slaughterhouse, and then they would have a more instructive time. Yet Jacques was happy with his frog's brain. From the side of the table he took two copper wires attached at the other end to a brass rod that ran through a cork which was in turn used to seal a glass bottle coated inside and out with foil. 'Jacques! Jacques! It's time for dinner. Come to the table!' It was Tante Mathilde's voice; clearly Jacques had not heard the notary depart. He set down the electrodes and blew out the candle, then crossed the landing to the top of the almost-vertical wooden staircase and groped his way down by the familiar indentations of the plaster wall. His grandmother came into the parlour carrying a tureen of soup, which she placed on the table. Rebière and his wife, known to Jacques as Tante Mathilde, were already sitting down. Rebière drummed his knife impatiently on the wood while Grandmère ladled the soup out with her shaking hand. 'Take a bowl out to . . .' Rebière jerked his head in the direction of the door. 'Wait,' said Grand-mère. 'There's some rabbit, too.' Rebière rolled his eyes with impatience as the old woman went out to the scullery again and returned with a second bowl that she handed to Jacques. He carried both dishes carefully to the door and took a lantern to light his way out into the darkness, watching his feet on the shiny cobbles of the yard. At the stable, he set down the food and pulled back the top half of the door; he peered in by the light of the flame and felt his nostrils fill with a familiar sensation. 'Olivier? Are you there? I've brought dinner. There's no bread again, but there's soup and some rabbit. Olivier?' There was a sudden noise from the horse, like the rumbling clatter of a laden table being overturned, as she shifted in the stall. 'Olivier? Please. It's raining. Where are you?' Wary of the horse, who lashed out with her hind legs if frightened, Jacques freed the bolt of the door himself and made his way into the ripe darkness of the stable. Sitting with his back to the wall, his legs spread wide apart on the dung-strewn ground, was his brother. 'I've brought your dinner. How are you?' Jacques squatted down next to him. Olivier stared straight ahead, as though unaware that anyone was there. Jacques took his brother's hand and wrapped the fingers round the edge of the soup bowl, noticing what could be smears of excrement on the nails. Olivier moved his head from side to side, thrusting it back hard against the stable wall. He muttered something Jacques could not make out and began to scrape at his inner forearm as if trying to rid himself of a bothersome insect. Jacques took a spoonful of the soup and held it up to Olivier's face. Gently, he prised open his lips and pushed the metal inwards. It was too dark to see how much went into his mouth and how much trickled down his tangled beard. 'They want me to come, they keep telling me. But why should I go, when they know everything already?' 'Who, Olivier? Who does?' Their eyes met. Jacques felt himself summed up and dismissed from Olivier's mental presence. 'Are you cold? Do you want more blankets?' Olivier became earnest.'Yes, yes, that's it, you've got to keep warm, you've to wrap up now the winter's coming. Look. Look at this.' He held up the frayed horse blanket beneath which he slept and examined it closely, as though he had not seen it before or had suddenly been struck by its workmanship. Then his vigour was quenched again and his gaze became still. Jacques took his hand. 'Listen, Olivier. It's nearly a year now that you've been in here. Do you think you could try again? Why don't you come out for a few minutes? I could help.' 'They don't want me.' 'You always say that. But perhaps they'd be happy to have you back in the house.' 'They won't let me go.' Jacques nodded. Olivier was clearly talking of a different 'they', and he was too frightened to contradict or to press him. He had been a child when Olivier, four years the older, started to drift away from his family; it began when, previously a lively and sociable youth, he took to passing the evenings alone in his room studying the Bible and drawing up a chart of 'astral influences'. Jacques was fascinated by the diagrams, which Olivier had done in his clever draughtsman's hand, using pens he had taken from the htel de ville, where he worked as a clerk. Jacques's experiences had usually come to him first through the descriptions of Olivier, who naturally anticipated all of them. Mathematics at school were a jumble of pointless signs, he said, that made you want to cry out; being beaten by the master's ruler on the knuckles hurt more than being kicked on the shin by the broody mare. Olivier had never been to Paris, but Vannes, he told Jacques, was so huge that you got lost the moment you let your concentration go; and it was full of women who looked at you in a strange way. When changes came to your body, Olivier said, you noticed nothing, no hairs bursting the skin, no wrench in your voice; the only difference was that you felt urgent, tense, all the time, as though about to leap a stream or jump from a high rock. Olivier's chart of astral influences therefore looked to Jacques like another early glimpse of a universal human experience granted to him by his elder brother. Olivier had been right about everything else: in Vannes, Jacques kept himself orientated at all times, like a dog sniffing the wind; he liked mathematics, though he saw what Oliver had meant. He avoided the master's beatings. 'Where is God in this plan?' he had said, pointing with his finger. 'I see the planets and their influence and this character, here, whatever his name is. But in the Bible, it says that-' 'God is here, in your head.And here.' Olivier pointed to the chart. 'But it's a secret.' 'I don't understand,' said Jacques. 'If this is Earth here, this is Saturn, and here are the rings of Jupiter and this is the body you've discovered, the one that regulates the movements of people, then what are these lines here? Are these the souls of the dead going up to Heaven?' 'Those are the rays of influence. They emanate from space, far beyond anything we can see. These are what control you.' 'Rays?' 'Of course. Like rays of light, or invisible waves of sound. The universe is bombarded with them.You can't hear them.You can't see them.' 'Does everyone know about them? All grown-ups?' 'No.' 'How do you know about them? Who told you?' 'I have been told.' Jacques looked away. Over the weeks, he discovered that Olivier's system of cosmic laws and influences was invulnerably cogent; there was in fact something of the weary sage in his manner when he answered yet another of Jacques's immature questions about it, while its ability to adapt made it impermeable to doubt. Olivier was always right, and his rightness was in the detail. Jacques was not sure that this next phase of his education, these rays and planets into which Olivier was inducting him, was one he welcomed. He believed in what he learned at church and in what the Curé told him later in their walks through the woods and down to the sea. At least, he thought he did; he believed that he believed. 'Would you like some of the rabbit? Grand-mère cooked it.' Jacques wanted the company of his brother but shrank from sitting in the fouled straw. 'Don't you want a bath, Olivier? Would you like to wash?' 'I take my bath in the sea.' 'You haven't been to the sea for-' 'The water runs clear . . . Always clear.' 'What do you do all day, Olivier? When I go out to work for Papa?' He felt Olivier's breath on his cheek. 'That's the trouble with the army. No time to yourself.You're up at six, and it's stand-to at six fifteen. They've sent all my clothes back to Rennes . . . But you shouldn't stand there, that's not your place.' Jacques said nothing. He had the feeling that, although there was no one else in the stable, it was not to him that Olivier was addressing his remarks. He became impatient when Jacques tried to break in; he seemed frightened of displeasing the absent person by failing to pay full attention to their shared conversation. Olivier grew agitated. 'Don't stand there. That's his place.You're always in the way.Why don't you learn to do what you're told?' He stood up and grabbed a metal bucket from the ground next to the horse's stall. Jacques thought he was going to throw it, but the strength seemed to leave him again, and he dropped the bucket as he slumped back into his original position, with his back to the wall. He was silent, though his limbs were still agitated as he moved his head from side to side. Jacques had not lost his brother; he had not woken up one day to find him gone. Rather, Olivier had stolen away, little by little, like smoke beneath the door; and it had happened so slowly that there seemed no moment at which Jacques could have said, 'He's gone.' It was still occasionally possible to talk to him and feel that something was transmitted and received, though more often Olivier's ear seemed tuned to other tones, the commandments of ancestral voices. Jacques did not understand what had happened. He wanted to believe in the universe his brother described; he wanted to see the logic or the plan - to share and understand them so that he could have his confidant again: he was lonely without Olivier and he no longer had a guide to what lay ahead of him. Other people of his own age did not interest him; compared to the intimacy he had shared with Olivier, their offered friendship was useless. 'I must go back to dinner now,' he said.' I'll come back for the plates tomorrow.' Jacques went to the door and picked up the lantern where he had left it on the floor because Olivier was not allowed a flame. He turned in the rain outside and bent his hand over the half-door to slide the bolt. In the light of the lantern he could just make out the shape of his brother in the darkness. He sat with his back to the wall, his legs spread wide in front of him, his head nodding expressively as he reasoned with an unseen companion. Two hens fluttered on the rafter above him. Between the flame outside and the square of darkness within, were the pinpoints of the tumbling drizzle. Beyond them, Olivier looked like a prophet from the Old Testament, his hair uncut for more than a year, his dark beard reaching almost to his chest. The piled bales of straw behind him made a ragged arch of steps, like the burial place of a minor potentate, hoping to be gathered up more easily to heaven.Two bridles dangled from a wooden post like effigies in the church of an obscure religion; and the function of such things seemed altered, thought Jacques, as though Olivier's experience had somehow reset the surroundings in the light of its own integrity. On the other side of the stable wall, the pig grunted and moaned in its sty; Jacques turned from the door, his eyes wet, aware of something absent from his understanding of the world as he hurried back towards his father's house. From the Hardcover edition.

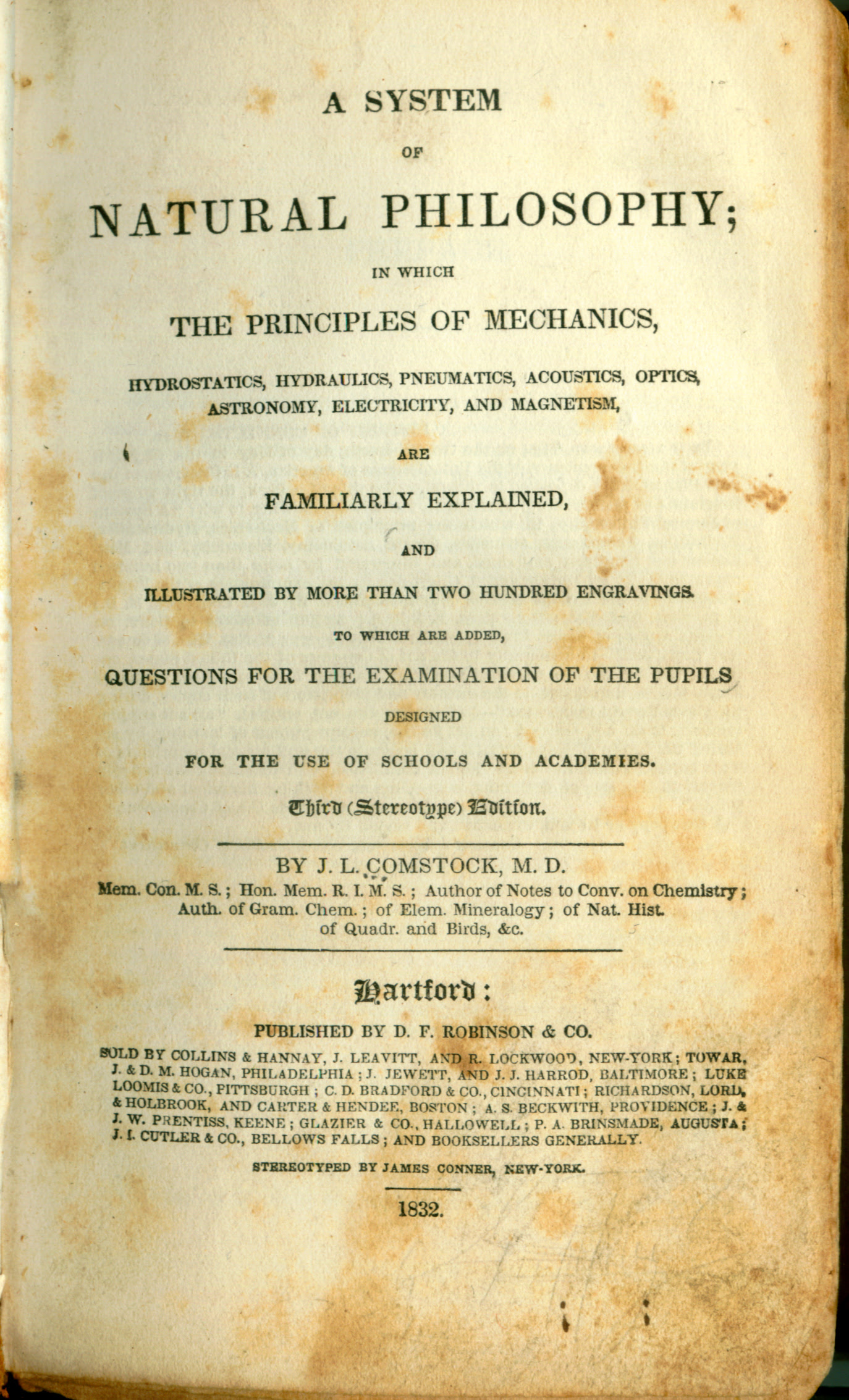

Publication Details

Title:

Author(s):

Illustrator:

Binding: Paperback

Published by: Vintage Books: , 2006

Edition:

ISBN: 9780099458265 | 0099458268

618 pages.

Book Condition: Good

Cover worn

Pickup available at Book Express Warehouse

Usually ready in 4 hours

Product information

New Zealand Delivery

Shipping Options

Shipping options are shown at checkout and will vary depending on the delivery address and weight of the books.

We endeavour to ship the following day after your order is made and to have pick up orders available the same day. We ship Monday-Friday. Any orders made on a Friday afternoon will be sent the following Monday. We are unable to deliver on Saturday and Sunday.

Pick Up is Available in NZ:

Warehouse Pick Up Hours

- Monday - Friday: 9am-5pm

- 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon NZ

Please make sure we have confirmed your order is ready for pickup and bring your confirmation email with you.

Rates

-

New Zealand Standard Shipping - $6.00

- New Zealand Standard Rural Shipping - $10.00

- Free Nationwide Standard Shipping on all Orders $75+

Please allow up to 5 working days for your order to arrive within New Zealand before contacting us about a late delivery. We use NZ Post and the tracking details will be emailed to you as soon as they become available. There may be some courier delays that are out of our control.

International Delivery

We currently ship to Australia and a range of international locations including: Belgium, Canada, China, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, United States, Hong Kong SAR, Thailand, Philippines, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden & Singapore. If your country is not listed, we may not be able to ship to you, or may only offer a quoting shipping option, please contact us if you are unsure.

International orders normally arrive within 2-4 weeks of shipping. Please note that these orders need to pass through the customs office in your country before it will be released for final delivery, which can occasionally cause additional delays. Once an order leaves our warehouse, carrier shipping delays may occur due to factors outside our control. We, unfortunately, can’t control how quickly an order arrives once it has left our warehouse. Contacting the carrier is the best way to get more insight into your package’s location and estimated delivery date.

- Global Standard 1 Book Rate: $37 + $10 for every extra book up to 20kg

- Australia Standard 1 Book Rate: $14 + $4 for every extra book

Any parcels with a combined weight of over 20kg will not process automatically on the website and you will need to contact us for a quote.

Payment Options

On checkout you can either opt to pay by credit card (Visa, Mastercard or American Express), Google Pay, Apple Pay, Shop Pay & Union Pay. Paypal, Afterpay and Bank Deposit.

Transactions are processed immediately and in most cases your order will be shipped the next working day. We do not deliver weekends sorry.

If you do need to contact us about an order please do so here.

You can also check your order by logging in.

Contact Details

- Trade Name: Book Express Ltd

- Phone Number: (+64) 22 852 6879

- Email: sales@bookexpress.co.nz

- Address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, 4821, New Zealand.

- GST Number: 103320957 - We are registered for GST in New Zealand

- NZBN: 9429031911290

We have a 30-day return policy, which means you have 30 days after receiving your item to request a return.

To be eligible for a return, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unread.

To start a return, you can contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz. Please note that returns will need to be sent to the following address: 35 Nathan Terrace, Shannon, New Zealand 4821.

If your return is for a quality or incorrect item, the cost of return will be on us, and will refund your cost. If it is for a change of mind, the return will be at your cost.

You can always contact us for any return question at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.

Damages and issues

Please inspect your order upon reception and contact us immediately if the item is defective, damaged or if you receive the wrong item, so that we can evaluate the issue and make it right.

Exceptions / non-returnable items

Certain types of items cannot be returned, like perishable goods (such as food, flowers, or plants), custom products (such as special orders or personalised items), and personal care goods (such as beauty products). Although we don't currently sell anything like this. Please get in touch if you have questions or concerns about your specific item.

Unfortunately, we cannot accept returns on gift cards.

Exchanges

The fastest way to ensure you get what you want is to return the item you have, and once the return is accepted, make a separate purchase for the new item.

European Union 14 day cooling off period

Notwithstanding the above, if the merchandise is being shipped into the European Union, you have the right to cancel or return your order within 14 days, for any reason and without a justification. As above, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. You’ll also need the receipt or proof of purchase.

Refunds

We will notify you once we’ve received and inspected your return, and let you know if the refund was approved or not. If approved, you’ll be automatically refunded on your original payment method within 10 business days. Please remember it can take some time for your bank or credit card company to process and post the refund too.

If more than 15 business days have passed since we’ve approved your return, please contact us at sales@bookexpress.co.nz.